Masks and Metamorphosis

Virtual Realities, True Selves

10/26/20237 min read

Halloween is nearly upon us, and for North Americans especially, this is one of the only days of the year in which the wearing of a costume by adults is broadly accepted. It is to their detriment that so many do not understand that they can dress up whenever they wish, but instead wait to be granted permission by society at large to assume alternate guises which they are otherwise shamed to don at any other time. Assuming alternate appearances and roles without a collectively sanctioned reason is commonly viewed as behaviour suited only to children, criminals, and the very strange. And so even on a day set aside for it, they cannot indulge seriously, but play it as a laugh, or a caricature, and this is why what they wear is mere costume and not something more revealing. It is the default assessment that the wearing of a mask or costume is concealing the true self beneath, but this a superficial view (skin deep, if you will) and here we will instead consider that rather, the removal of the outward presentation that is imposed on us by society permits the true expression of the inward self

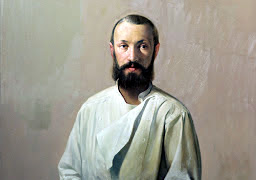

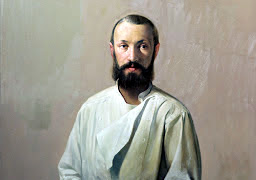

This idea of the inward (private) and outward (public) self is something explored by the Russian philosopher and literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin (1895-1920). Bakhtin introduced or adapted several important ideas to literary thought, which spring from his concept of heteroglossia. Most simply stated, this is the existence of two or more independent, unique, and potentially conflicting “languages,” or voices, within discourse. Following this we have polyphony1 and the dialogical, which again present a multiplicity of views as opposed to the monological, which asserts a fixed viewpoint (i.e. that of the author). These are mentioned here as mere prologue to what really concerns us, and that is his concept of the carnivalesque.

Carnivalesque, as one can guess, references that like to the carnival, but it is important to distinguish that when we speak here of “carnival,” we do not refer to the tents, sideshows, and rides of mobile amusement, but the various masking festivals throughout the world and history in which the participants, for a time, suspend the usual social rules and norms.2 In order for this to happen there must be tension between the expected and the desired, the public and private, or the exterior and interior life. The roles imposed upon us by class are often at odds with who we see ourselves to be or wish to be seen or behave, and carnival creates an environment in which the collective laughter of the people mocks the absurdity of established authority, challenging the accepted vertical hierarchy in favour of a horizontal collective. As Bakhtin says, “In the world of carnival all hierarchies are canceled. All castes and ages are equal.”3

And the means whereby this social inversion or flattening occurs is through the wearing of masks. But let us not confine ourselves to the concept of the mask as strictly a face covering. We wear masks every day, in the form of our clothing, makeup, accessories, even in the manner of our speech. We apply these things differently for work, than we do for the street, than we do for a formal event. So while we may tend to think of our appearance as unchanging, our physical form undergoes frequent, ongoing, and sometimes radical change through our own manipulation, aging, environment, and trauma. Does the mask then create an illusion, or dispel one? Conceal one's true nature or bring it to the surface? Costume and disguise are invariably associated with the former, concealing the wearer's "true" appearance, and within the events of carnival, concealing the self, or even becoming invisible can have great appeal when committing mischief. This of course is the standard accusation put forth, that disguise is by default concealing and concealment in Western culture is traditionally viewed as dishonest. In liminal spaces however, such as the carnival-goer navigates, the mask is a revealing communicative tool between this world and other worlds, making that which is unseen, visible.

And so we at last come to Social VR, where we wear masks! Sometimes fixed, sometimes ever changing, but a representation of how we wish to appear. That mask is the avatar, and unlike a physical mask, its virtual nature allows outward expression without constraints on movement, breathing, or vision. These are factors which performers and actors who may be confined within layers of silicone and makeup can find themselves (unwittingly or intentionally) mentally transformed through the physical stimuli of their new skin. While the virtual headset/HMD (if applicable) applies a different set of inputs which may influence how we perceive and present ourselves, overall an avatar is a mask we wear more than it wears us.

Is Social VR a carnival? No, but it is reasonable to call it carvivalesque, where the masked revelers assemble, often regularly and frequently in an alternate reality that provides a carnival-like atmosphere. In the best tradition of on-line communities it is constructed by the users for the users. It is very much as Bahktin says, that:

“The carnivalesque crowd in the marketplace or in the streets is not merely a crowd. It is the people as a whole, but organized in their own way, the way of the people. It is outside of and contrary to all existing forms of the coercive socioeconomic and political organization, which is suspended for the time of the festivity.”4

The marketplaces and streets may be virtual, but their function is the same in bringing disparate persons together, who would otherwise never or only reluctantly interact. In this shared plane of existence, they converse and play with a familiarity brought about by curiosity, fellowship, and joy, rather than compulsion. Eschewing the uniform of daily, exterior life and assuming the mantle of interiorness, they come to find themselves more easily bound to one another.

“This festive organization of the crowd must be first of all concrete and sensual. Even the pressing throng, the physical contact of bodies, acquires a certain meaning. The individual feels that he is an indissoluble part of the collectivity, a member of the people’s mass body. In this whole the individual body ceases to a certain extent to be itself; it is possible, so to say, to exchange bodies, to be renewed (through change of costume and mask). At the same time the people become aware of their sensual, material bodily unity and community.”5

What Bakhtin is so poetically describing here might very well be the Social Identity Model of Deindividuation Effects (SIDE). This views a person’s identity as being composed of one’s own perception along with a number of other identities which are based on group memberships and identifying characteristics, such as national origin, race, and gender, as well as school, workplace, or organizational affiliation. When these associations are stripped away some interesting things occur. Firstly, the classical view describes this as deindividuation, and concludes that “individuals in a deindividuated state lose all behavioral constraints imposed by social norms.”6 This might make for a fun party but could also be seen negatively, though more current research takes a more positive angle! Rather than deindividuation, the SIDE model now prefers the term depersonalization to contrast these findings that demonstrate a “positive relationship between anonymity and conformity.” Instead of finding themselves de-regulated, individuals who no longer have clear group associations can in fact develop greater levels of self-regulation and conformance to their (new) group. So that “when placed in a group, people with obscure personal cues are more likely to identify themselves as part of a group, rather than as a unique individual.”7

If you're a social VR enthusiast then this no doubt sounds familiar. Despite the potential for utter chaos (and there is no denying it exists) a surprising majority of individuals tend to moderate themselves in accordance with the expectation of the space. You have also likely experienced yourself or talked to people who believe that sharing and openness is more pervasive in Social VR and that people are willing to express themselves more freely or openly discuss their personal feelings. On the surface we might assume that our presumed anonymity fosters this state by divorcing us from consequence or embarrassment, but this is less convincing when we consider these interactions are not so fleeting as a few debauched evenings but often take on complex and complete alternate lives. How often must one wear a mask for it to simply become an identity? If others know you only by that mask, who else are you to them but what they see? “Looking like someone else and being someone else are completely different things,” you might argue, and so too does Scully of X-files fame. But in response Mulder gives us something to consider, that “everybody else around you would treat you like you were somebody else, and ultimately maybe it's other people's reactions to us that make us who we are.”8

As a final thought, the existence of masquerades, Halloween parties, and other events within Social VR where costumes are encouraged further reinforces that the avatar itself is not a costume but very much an outward expression of self. The very language used in referencing a costume requires that it be a temporary mask, and what then is the avatar but our face? This layering of mask upon mask adds yet another dimension to the transformative nature of our exterior presentation upon others, and cyclically, our interior selves.

1“The essence of polyphony lies precisely in the fact that the voices remain independent and, as such, are combined in a unity of a higher order than in homophony. If one is to talk about individual will, then it is precisely in polyphony that a combination of several individual wills takes place, that the boundaries of the individual will can be in principle exceeded. One could put it this way: the artistic will of polyphony is a will to combine many wills, a will to the event.” Bakhtin, Mikhail. Essay. In Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, 21. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984.

2Venice, Rio de Janeiro, and New Orleans are home to the most well-known.

3Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984), 125.

4Rabelais and His World pp255

5Ibid

6Huang, Guanxiong. “The Effect of Anonymity on Conformity to Group Norms in Online Contexts: A Meta-Analysis.” International Journal of Communication 10 (2016): 398–415.

7Ibid

8 X-files,"Small Potatoes," April 20, 1997.